EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

In order to contribute to the promotion of fundamental freedoms with the support from the United Nations Democracy Fund (UNDEF), “Strengthening Local Capacity to Improve Policies in Cambodia” project has implemented its activities in 252, villages, 35 commune, 18 districts of 8 target provinces: Siem Reap, Kampong Cham, Preah Vihear, Ratanakiri, Banteay Meanchey, Battambang, Mondulkiri and Kampong Chhnang provinces, covering key activities such as: conducting training courses on fundamental freedoms, advocacy and networking, meetings with commune / sangkat and provincial authorities, organizing regional and national workshops.

Through the implementation of a series of activities including the national workshop, the project has uncovered some of the following findings to submit to the relevant ministries and institutions to explore specific, peaceful and harmonious solutions for the people in the community:

– Communities’ 17 challenges related to fundamental freedoms, 14 responses from the sub-national authorities, and 26 suggestions (recommendations) from the communities.

– H.E. Katta On of the Cambodian Human Rights Committee (CHRC) has promised to raise the 17 challenges and the 26 recommendations (suggestions) in the agenda of the Inter-Ministerial Meeting of the Cambodian Human Rights Committee, which consists of 20 relevant ministries. In particular, His Excellency will organize a meeting with the six relevant ministries to explore the possibility of resolving those challenges for the people. The six relevant ministries/institutions are: Ministry of Interior, Ministry of Justice, Ministry of Land Management, Urban Planning and Construction, Ministry of Environment, Ministry of Agriculture (Forestry Administration) and Apsara Authority.

– Representatives of both civil society organizations, LICADHO’s General Manager, and the Executive Director of the Cambodian Center for Human Rights, fully agreed with the findings, challenges and recommendations regarding ADHOC’s fundamental freedoms.

– Request the Cambodian Human Rights Committee to help remove some content in the White Book produced by the Office of the Council of Ministers, which implicates some civil society organizations with color revolution… This has triggered local authorities to

-1-

tighten and monitor all activities of the organizations, especially those listed in the White Book.

– By participating in debate activities from the commune/sangkat to the provincial levels, local authorities seem to have already recognized their actions upon the uncovering of the 17 community challenges, said ADHOC’s Director.

More information:

- Mr. Meas Savath, Secretary General of ADHOC, 086 385 666

- Mr. Soeung Sen Karuna, Spokesman and Duputy Director in charge of Human Rights and Land Rights, 086 324 666

REPORT

- Introduction

ADHOC is the first Cambodian human rights association founded on December 10, 1991 for advocating human rights and democracy, was officially recognized and approved by Samdech Preah Norodom Sihanouk on March 10, 1992, and was officially recognized by the Ministry of Interior, through Prakas No. 278, dated March 28, 2000. ADHOC has been carrying out key activities such as local community empowerment, advocacy and monitoring and interventions related to abuses of human rights, land rights, and the rights of women and children.

“Strengthening Local Capacity to Improve Policies in Cambodia” project aims to promote the rights of local communities to participate in public debates through the development and enhancement of knowledge of human rights, fundamental freedoms, networking, advocacy skills and the ability to get their voices heard in order to restore a culture of dialogue between local communities and sub-national and national government agencies and to contribute to policy improvements to ensure the promotion of democracy and respect for human rights in Cambodia.

2. Project overview

Root causes: In recent years, after the 2013 national election, the decline in respect for human rights and fundamental freedoms has been seen as having profound effects on democratic process, sustainable development and poverty reduction. Freedom House’s 2019 Freedom Report ranks Cambodia as a “non-free country” and the country lost four points between 2017 and 2018, marking one of the most significant declines in the world

Restrictions on civil society and fundamental freedoms are hindering Cambodia’s progress, especially among poor communities and people with disabilities living in remote areas who possess little knowledge of their fundamental rights and freedoms, thus disabling them from getting involved in democratic development and they become very vulnerable to human rights abuses. These factors are at odds with United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDG)’s

Target 16.7: “Ensure responsive, inclusive, participatory and representative decision-making at all levels.”; Target 16.10: “ensure public access to information and protect fundamental freedoms, in accordance with national legislation and international agreements”; Goal 1: End poverty in all its forms everywhere”; Goal 5: “Achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls; and ADHOC has identified the following three key problems:

– Problem 1: Lack of skilled knowledge of advocacy and local community networking

– Problem 2: Communication – provision and reception of information remains unclear among local communities to express their concerns and challenges and give recommendations to local, provincial and national authorities.

– Problem 3: Space for culture of dialogue between local community members to share their concerns, challenges and recommendations with national and local authorities is still limited.

To participate in the development and promotion of democracy, especially fundamental freedoms, with funding support from the United Nations Democracy Fund (UNDEF), Adhoc has implemented its activities in 252, villages, 35 commune, 18 districts of 8 target provinces: Siem Reap, Kampong Cham, Preah Vihear, Ratanakiri, Banteay Meanchey, Battambang, Mondulkiri and Kampong Chhnang provinces, covering 06 key activities such as: conducting training courses on fundamental freedoms, advocacy and networking for 1,225 community representatives from 35 communes/sangkats; meetings with local authorities, with main focuses on fundamental freedoms; meetings with provincial authorities, discussing communities’ challenges and recommendations which have not been clearly addressed; regional workshops which continued to discuss with the communities about the challenges, recommendations, and unclear solutions from the provincial authorities in order to design

strategic plans and collect inputs for further discussion at the national workshop; and update meeting with national authorities in order to continue the discussion of the national workshop’s report.

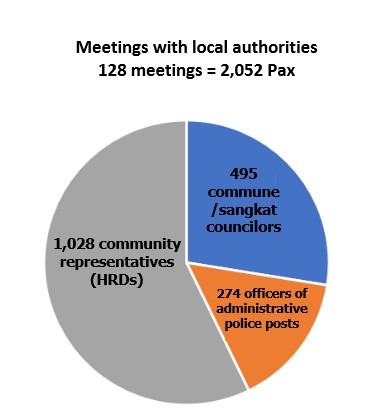

128 meetings among community representatives

128 meetings among community representatives

and local authorities within 35 communes/sangkats of 8

target provinces. These meetings presented opportunities

for the community to raise various issues happening

within their communities, especially to directly raise their

concerns, challenges, recommendations to the local

authorities to explore specific solutions. These meetings

were attended by a total of 2,052 participants which

included 1,028 community representatives (600 were

women, 383 young adults, and 559 members of

indigenous people), 495 commune/sangkat councilors,

and 274 officers of administrative police posts.

According to the analysis, only 15% of the issues raised by the community were responded, while the remaining issues and recommendations were prepared for further discussion at the provincial level.

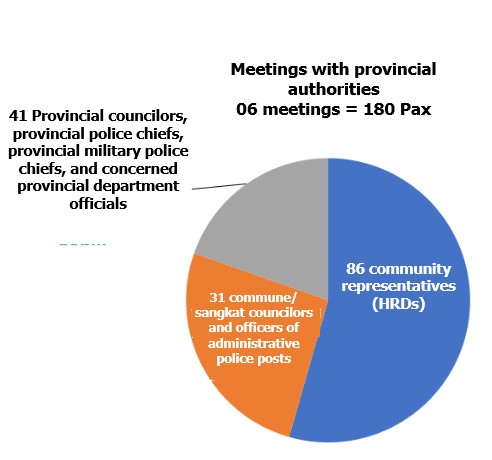

06 meetings with provincial authorities of the 8 target provinces. These meetings allowed

community representatives to raise issues which had not yet been resolved during their

meetings with local authorities for further discussions to find the solutions. These

meetings were attended by 86 community representatives, 41 deputy provincial governors, deputy provincial police chiefs, provincial

military police, and officials from the concerned provincial departments, and 31

commune/sangkat councilors and officers of the administrative police posts.

According to the analysis, only 20% of the issues were responded, while the remaining issues and recommendations were updated for further discussion at regional workshops before being discussed at the national level. According to the report, reasons that led to failure in organizing meetings with two provinces include:

– Preah Vihear province: The provincial governing board lacks cooperation, trying not to coordinate these meetings to happen, even if ADHOC, through its letters, had tried to seek for their cooperation and invite them to the meetings. For more than two

weeks, the provincial administration did not respond to our letters and repeated phone calls and we did not see them at their offices on many occasions of our attempts to see them.

– Battambang province: Because the provincial governing board and many officials were so busy with improving the party performance ahead of the commune/sangkat elections that they could not have time to have the meetings.

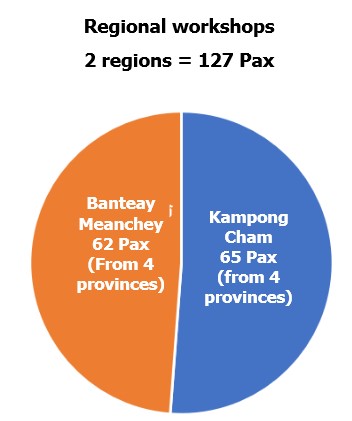

02 regional workshops were attended by 127 representatives of 35 local communities of 8 target provinces. The first workshop was held in Kampong Cham province with 65 participants (including representatives from the United Nations) from 4 provinces: Ratanakiri, Kampong

02 regional workshops were attended by 127 representatives of 35 local communities of 8 target provinces. The first workshop was held in Kampong Cham province with 65 participants (including representatives from the United Nations) from 4 provinces: Ratanakiri, Kampong

Cham, Mondulkiri and Siem Reap, and the second workshop was held in Banteay Meanchey, with a total of 62

participants from 4 provinces: Kampong Chhnang, Battambang, Preah Vihear and Banteay Meanchey.

These workshops provided an opportunity for local community representatives to share with other participants their concerns and challenges related to their fundamental freedoms and the  opportunity for them to work together to provide recommendations to the government on

opportunity for them to work together to provide recommendations to the government on

continuing to explore solutions for their challenges and to develop strategic advocacy plans for the national workshop.

From the 128 meetings at the local level, 06 meetings at the provincial level and 02 regional workshops, inputs were collected and consolidated for the national workshop which was attended by concerned ministries, in particular, the Ministry of Interior and Ministry of Justice, to explore the solutions. The inputs collected after the sub-national authorities failed to locate the solutions include: the challenges and recommendations of the local communities and the action plans developed by the communities which sought for changes and approval from the government:

01 National Workshop: It was a two-day (23-24 August, 2022) workshop at Sunway Hotel, with a total number of 143 participants (49 women), which included 113 community representatives, 24 civil society organizations’ staff members, 05 social media journalists, and

01 representative from the Cambodia Human Rights Committee (representatives from the Ministry of Interior and Ministry of Justice were absent).

These workshops achieved remarkable results: 17 community challenges, 14 sub-national authority responses and 26 community suggestions (recommendations), and the representative of the Human Rights Committee made a promise to include these findings in

These workshops achieved remarkable results: 17 community challenges, 14 sub-national authority responses and 26 community suggestions (recommendations), and the representative of the Human Rights Committee made a promise to include these findings in

the agenda of discussions among the human rights technical group which is composed of 20 inter-ministerial representatives to find solutions for the communities. Meanwhile, the representative of the Cambodian Center for Human Rights and the Cambodian League for the

Promotion and Defense of Human Rights, LICADHO, fully agreed with ADHOC’s findings, while the President of ADHOC stressed that by participating in local and provincial meetings, the authorities have acknowledged the challenges and suggestions (recommendations) raised by

the local communities and have made responses to certain challenges. General issues: Those issues are related to infrastructure and access roads in the communities, health and sanitation, security and safety in the villages and communes, migration, illegal fishing, land disputes involving powerful and wealthy elites, illegal encroachment of protected forests, closure of Trapaing Thmor reservoir which affected the farming activities of the nearby farmers, domestic violence, declining livelihoods, poverty and inability to pay loans.

2. Authorities threatened people with imprisonment warning! If people attended a meeting or a course with an organization, they must report to the authorities when attending a meeting related to filing a land dispute complaint.

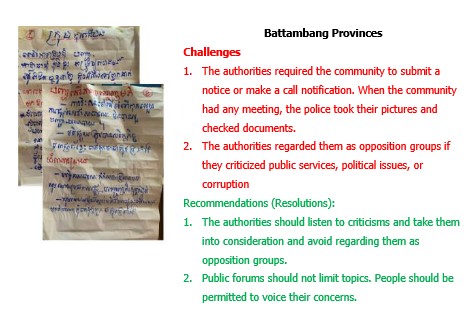

3. Some local authorities considered any community which dared to give constructive criticisms on public service delivery inactivity or dared to talk about corruption as an opposition group.

4. Local authorities restricted communities from speaking or complaining about land disputes or forest issues.

5. The authorities prevented the communities from filing petitions with the provincial administrations or the ministries.

6. The authorities failed to maintain the confidentiality of the communities’ members when they reported about various crimes, putting their personal security and safety at risk, so they no longer dared to report any further.

7. Political expression was restricted and intimidated by the authorities.

8. Authorities did not provide opportunities for dissidents to participate.

9. Commune councils have not yet cooperated in allowing communities to attend their monthly meetings.

10. Authorities restricted and discriminated against communities in engaging with civil society and political activities (eg: surveillance, interrogation, taking pictures, intimidation) by accusing and painting them with political party tendencies.

11. Village authorities restricted youth participation in various social activities, such as road repairs, sharing knowledge about the rights and roles of citizens.

at the local level and required prior notice and permission, demanded certified

documents, took pictures, listened to the meeting, and required our reports on

locations by sending them pictures of the activities.

13. Members of the communities were afraid to post messages about their political

opinions.

14. The Apsara Authority did not provide an appropriate solution to the request of the community regarding their housing rights.

15. The commune authorities threatened and brought the representatives for questioning after they raised land disputes in the meeting.

16. Environment officials in such provinces as Preah Vihear, Mondulkiri, Ratanakiri and Siem Reap did not allow communities to participate in monitoring and protecting public property.

17. When the communities saw and reported forest crimes to the commune authorities, they responded by saying there were no such crimes, and the commune authorities told them not spread this outside the community because the perpetrators were powerful.

1. The cooperative communities provided information to the authorities and asked the communities not worry when they saw authorities visit the villagers and seek for more information.

1. The cooperative communities provided information to the authorities and asked the communities not worry when they saw authorities visit the villagers and seek for more information.2. Requested for more frequent dialogue meetings between the communities and local authorities.

3. The communities helped disseminate the information about the rights and laws in the communities.

4. Enhanced good cooperation between the communities and authorities.

5. Local authorities cooperated with the communities in order to enhance the promotion

of knowledge regarding fundamental freedoms.

6. Put efforts in finding solutions in order to end discrimination against dissidents.

7. The authorities did not ban gatherings-dissemination meetings but asked the organizers to inform the local authorities to help ensure the security.

8. The request of the communities to attend the monthly meetings of the Commune/Sangkat Council is the rights and obligations of the people enshrined within the laws.

9. The commune authorities have never discriminated against dissidents, but expression of opinions must be genuine and should not hide any incitement purposes.

10. Village-commune authorities would prepare letters to invite community representatives to attend the monthly commune council meetings (after the COVID-19 ends).

11. Village-commune authorities did not restrict the rights and freedoms of assembly and expression because it is a citizen’s right, but they had internal fear.

12. The commune authorities would advise the village chiefs, but the youth groups must, in advance, inform the village chiefs clearly about the purpose of specific activities.

13. Because those activities were conducted without providing any prior notice to the authorities and it was during the COVID-19.

14. When the commune authorities and the officers from the administrative police posts asked them questions and took pictures of their activities, this was not a restriction or a threat to any rights or freedoms. In fact, this is not against the laws. If their activities complied with the laws, then they should not fear about being asked or taken pictures.

2. Suggest that the Ministry of Interior raise awareness and strengthen the capacity among local officials regarding the national laws, international laws, letters of notifications and other relevant provisions.

3. Suggest that the government issue instructions to local authorities to give better access for the citizens to attend public meetings with commune councils.

4. Suggest that the Ministry of Interior instruct the provincial authorities to give citizens the right to submit petitions and other complaints without prohibition and obstruction.

5. The Forestry Administration should help accelerate the establishment of community forests in Anchanh Roung and Pich Changva communes, Kampong Chhnang province and in Choam Ksan district, Chhep district and Tbeng Meanchey district of Preah Vihear province.

6. National and sub-national authorities must ensure that people have the right to express themselves without fear with an aim to develop the communities.

7. The authorities should have good cooperation with the people to find solutions, support and encourage all interventions.

8. Village-commune authorities should not restrict but respect fundamental rights and freedoms, especially freedom of expression and assembly – for those who they consider to have the opposite views.

9. The authorities should be more open-minded and give opportunities for community representatives to attend monthly commune council meetings, and should not wait until after the end of Covid pandemic.

10. The authorities should maintain confidentiality, personal security and safety of those who reported them any suspected crimes.

11. The authorities should be neutral and impartial, should not discriminate against political tendency and stop smearing.

12. Suggest that the authorities listen to the opposite views and take the views into consideration without classifying them as the opposition groups.

13. The Ministry of Interior should issue a directive to local authorities, advising them to stop monitoring, interrogating, photographing, requesting a list of community activities and requiring the community members to report them before and after participating

in activities with civil society organizations.

14. The National Authority for Land Dispute Solutions, Apsara Authority, and Ministry of Land Management should promote community participation in resolving housing issues.

15. The Ministry of Interior should issue notice to local authorities regarding freedom of political participation and political campaign during elections.

16. Commune authorities must abide by the laws and instructions from the Ministry of Interior regarding the activities of civil society organizations.

17. Provincial authorities should deal with local authorities regarding their perceived threats against community representatives who expressed their views.

18. The Ministry of Interior should increase additional commune budgets to assist community fisheries in maintaining and conserving natural resources.

19. At Commune/Sangkat Council meetings, the authorities should provide opportunities for the community to include problems of the communities in the meeting agendas.

20. The Ministry of Interior should instruct local authorities to understand the so-called defamation, agitation and incitement before filing lawsuits against those who post comments on Facebook about land disputes and forest issues.

21. The authorities should work with the communities to protect and conserve the natural resources.

22. Commune/Sangkat authorities should widely disseminate information regarding the commune/sangkat’s budget, revenue, expenses.

23. The Ministry of Justice should set up offices which assist the people in writing the complaints and provide legal counselling for the local communities.

24. The authorities should notify, disseminate and encourage communities’ engagement in designing development or investment plans.

25. Environment officials must recognize the involvement of the Forest Defenders Network and grant better access for the network to participate in monitoring and protecting community forests.

26. Authorities must pay attention to all reported crimes and take preventive interventions in a timely and responsible manner.